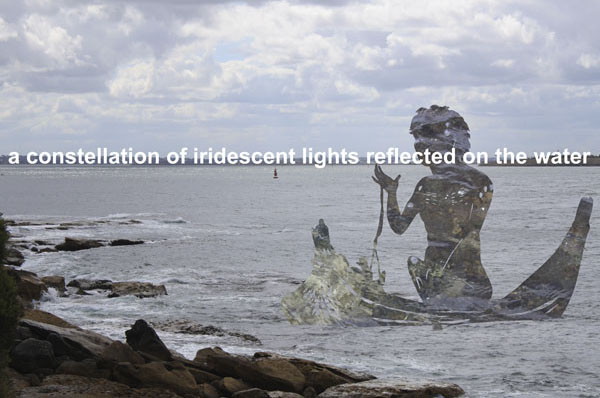

The project and print artwork Drawing the line between Stranger and Native explores the legacy of Botany Bay as white Australia’s foundational site. In April 1770, two vastly different civilisations met in a large estuary originally called Kamay (Gamay) when a sailing ship pulled up alongside people fishing from canoes. Official Australian History began on the thin stretch of sand they called Kundull. The site wears the consequences of this extraordinary encounter and the ensuing contest for justice, ownership and management.

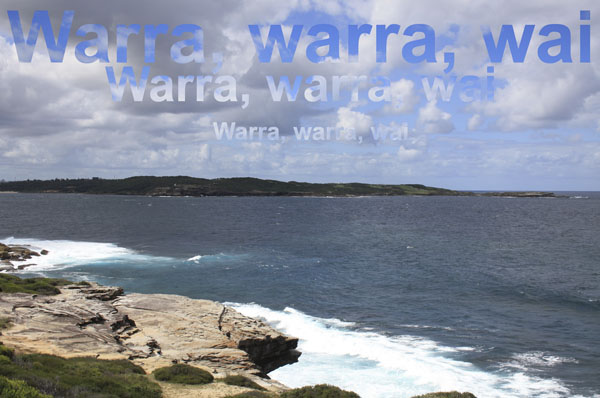

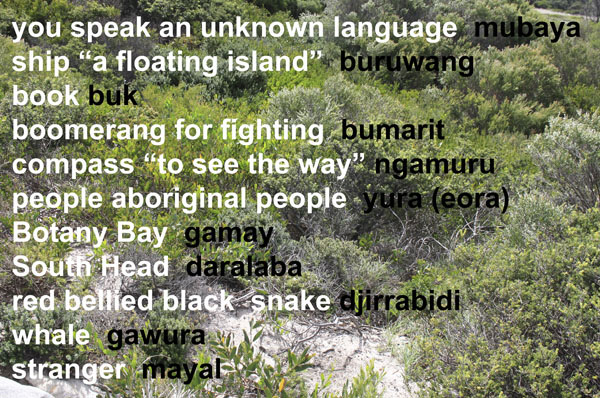

To the Strangers the Bay and the new South Continent was an utterly unknown place, a tabula rasa or blank slate. James Cook (aged 40), Joseph Banks (aged 26) and artist Sydney Parkinson (aged 19) write vividly about Botany Bay describing an infinite and mysterious nature waiting to reveal her secrets. Cook reflected in his Endeavour Journal that “They live in a Tranquillity which is not disturb’d by the Inequality of Condition: The Earth and sea of their own accord furnishes them with all things necessary for life”, to which, as Parkinson scrupulously observed, the Botany Bay clans responded in Dharawal language “Warra, warra, wai” meaning “go away”.

Drawing the Line 13, digital pigment print on watercolour paper, 42 x 58 cm

Artworks: Edition of 3 with 2 artist proofs

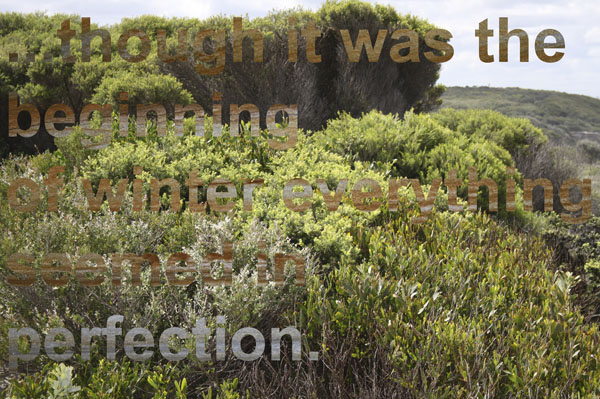

The Strangers ignored the injunction and fired warning shots, wounding a Native resister. They stayed in Botany Bay for eight days bathed in gentle autumn light, with Cook mapmaking and Banks and Solander, who learnt his botany from the Carl Linnaeus, gathering natural and ethnographic specimens. Sydney Parkinson sketched furiously and rapturously described a land where “though it was the beginning of winter everything seemed in perfection.” The accounts by Cook and Parkinson are open-minded and speculative. Perhaps Cook who did his apprenticeship on the Quaker-owned ship the Freelove shared a common public spirit with the Quaker, Sydney Parkinson. Aristocratic and wealthy Banks is more dismissive.

The Strangers’ speculation on the Native social structure is even more vexed than the wildly differing re-telling of the first encounter. Many assume the influence of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s On the Origins of Inequality (1753), an essay illustrating the concept of the Noble Savage. Rousseau, a believer in Plato’s Republic of select land-owning male citizens, asserts that the nasty side of the human condition—oppression, desire and pride—derives not from nature but society. French explorer Louis Antoine de Bougainville described Tahiti in such glowing terms, popularising Tahiti (or Otaheite as Banks correctly re-named it), as a paradise where men and women lived in innocence away from the corruption of civilisation. Arriving at Tahiti several years later, Cook’s expedition stayed for three months observing the Transit of Venus and all Journals harmonise with a rosy view despite the many misunderstandings.[1]

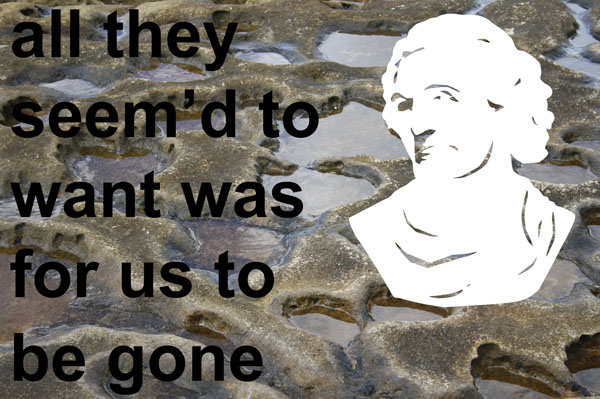

Tahiti was a leisurely encounter in a beautiful but ambiguous paradise confirming, to a point, Rousseau’s ideas of the Noble Savage. After Tahiti the Endeavour visited 17 other islands and circumnavigated the 2 islands of Aotearoa New Zealand, guided by Tupaia, who spoke highborn Tahitian and understood Maori language.[2] In contrast encounters along the eastern coastline of Australia were quick and tentative, the 8-days at the Bay being the sole sojourn excepting the forced stay to make repairs on the Endeavour River. On landing at Kundull Cook’s party found only empty dwellings. To conciliate they left beads, cloth and objects. In return they stole forty or fifty wooden implements. Not surprisingly Cook notes the Natives were both reclusive and hostile “and we were never able to form any connection with them”. Of the people they encountered Cook writes: “all they seem’d to want was for us to be gone”.[3] So successful was the Native non-engagement policy that Cook and Banks left puzzled and unable to account for the large number of fires along the coast with Cook incorrectly calculating fewer than fifty to sixty people lived around the bay’s shoreline. Cook did complete our modern image of the world and defeat the idea of a mythical southern continent.

James Cook, an expert navigator and cartographer, first chose the name Stingray Bay, perhaps as the crew were catching so many stingrays or because the bay is roughly shaped like a stingray with two tails formed by the Cook and Georges Rivers, but re-named it Botany Bay in deference to Banks’ enthusiasm.[4] Curator and writer Djon Mundine, seizes on this ‘off-record’ change—the diary shows the word Stingray ruled out and the new name inserted above—to note the unconscious distinction between salt and fresh water: the seaman sees saltwater (the stingray) and the wealthy botanist sees dry land plants (an estate). Both miss the crucial interrelation between fresh and saltwater and its significance in Aboriginal culture and society. Mundine is re-enacting the first encounter and makes the astute observation from Tribal Warrior Association’s ship Deerubbun on Survival Day, 26 January 2008. He speaks as an equally stern, but black, Captain Cook taking over Tupaia’s captaincy.[5]

An even bigger question about the nature of property and ownership lurked beneath Cook and Banks’ conflicting observations. As they head north to Torres Straight, they reflect (and perhaps confer) on these fleeting encounters and come close to the Noble Savage idea. I use Cook’s famous reflection “They live in a Tranquillity which is not disturb’d by the Inequality of Condition …”. Banks is more condescending: “Thus live there—I had almost said happy—people, content with little nay almost nothing.”[6]

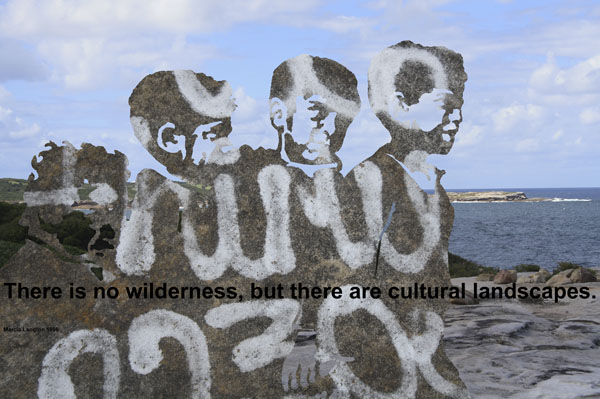

These insights added to later interpretation of the land as terra nullius, a wilderness open to claiming. Eighteen years later Banks, now President of the Royal Society, oversaw and legitimated the correctional convict settlement. The arrival of Governor Arthur Phillip and the First Fleet convict convoy was catastrophic. The foundation is and remains opposed to notions of geographic and regional legality. Botany Bay and Port Jackson rapidly became the epicentre of mass deaths from smallpox and other introduced disease and violence increasingly caused by competition for resources. These deaths and violence left deep scars on the memories and imagination of victims and perpetrators.

Phillip’s landing on 26 January is officially celebrated as Australia Day and unofficially as Survival Day. The implicit white suprematism of conquest has polarised into a jingoistic affair with the extremist riots at Cronulla Beach in December 2005 and on-going affrays to Australia Day ignited by toxic anti-refugee ‘border protection’ political stirring. Cronulla’s symbolic white sand/white Australia image gave vicious scenes of racial terror a global reach beyond a few days in the local media. In response to the sharp growth in nationalism and political acts expressing a neo-imperialist disregard for the independence and autonomy of peoples and places, many Australian artists have turned to the symbolism of the First Encounter. For examples of artists working on racism and refugee policy see exhibition catalogues Border Panic Reader, Performance Space, 2002, ed., Cassi Plate, and Lucky Country (still different), Hazelhurst Art Gallery, 2007, ed., Ron and George Adams. The echoing question about strategies to reclaim history is rephrased in the context of Ace Bourke’s research exhibition Lines in the Sand: Botany Bay Stories from 1770 (at Hazelhurst Art Gallery, 2008). My work, like that of the many artists in Lines in the Sand, is attentive to the two civilizations meeting at this line. [7]

Two museums commemorate First Contact at Botany Bay. Both museums include researched displays of Aboriginal history pre-contact, but there is no monument to Aboriginal history or consideration of the effects of the white invasion. Cook’s Landing Place and Museum at Kurnell is run by National Parks and Wildlife and at La Perouse there is a museum devoted to the French explorer Jean-Francois de Galaup, Comte de Laperouse at the site of his 1788 landing, five days after Phillip and the First Fleet. Journalist John Pilger dramatically highlighted the lack of Native voice and commemorative presence in the book and video Secret Country: The First Australians Fight Back (1985). Writer Bruce Dawe similarly asks in the poem For the Other Fallen, “You fought here for your country./ Where are your monuments?”[8]

Djon Mundine famously responded with the idea and realisation of The Aboriginal Memorial, a work by artists of Ramingining in Central Arnhem Land. The Memorial comprises 200 works—one for each year of occupation to 1988—that form a forest of dupun (painted hollow long bone coffins) and eloquently reclaims history, emerging in triumph as the nation’s cultural centrepiece and an acclaimed international masterpiece.[9] After 12 years of the History Wars (called in the US under President Bush the Culture Wars) fuelled and led by conservative Prime Minister John Howard, Mundine again takes up the discourse about a right to negotiate history:

“Finally after travelling full circle, today there are serious if somewhat forced recognitions of the natural beauty of the water and surrounds, and attempts to restore the environment; and connect and listen to Aboriginal people.”[10]

The logic of the meeting, proposed by Mundine, is diametrically opposed to the top-down rhetoric of the Federal Intervention into Northern Territory Aboriginal Communities now rebadged as a more working family friendly, Closing the Gap. This seems another case of re-naming to obliterate history and promote more of the same as a difference.

[1] Banks wrote a long anthropological essay ‘On the Manner and Customs of the South Sea Islands’ and amassed a private museum’s worth of Pacific Culture artefacts. Louis Antoine de Bougainville also published Voyage autour du monde, 1771. Denis Diderot’s, Supplément au voyage de Bougainville, retells Bougainville’s landing on Tahiti along with the description of the Tahitians as noble savages as a critique of Western ways of living and thinking.

[2] Adrienne Kaeppler, James Cook and the Exploration of the Pacific, Bonn Museum, Germany, 2009. Kaeppler notes that Cook and his men reported to Tupaia on this part of the voyage.

[3] Lt. James Cook, RN, Endeavour Journal, 30 April 1770.

[4] Cook, Journal, 29 April 1770.

[5] Ace Bourke, Lines in the Sand: Botany Bay Stories from 1770, 2008, Hazelhurst Art Gallery, p. 7.

[6] Cook, Endeavour Journal, 22 August 1770; Banks, Journal, August 1770, National Library of Australia at http://southseas.nla.gov.au/journals/banks/17700420.html

[7] Fiona MacDonald, Log Cabin—JCI, 2005, a woven print and artist statement, in Lines in the Sand, op cit., p. 52.

[8] Cited in K.S Inglis assisted by Jan Brazier, Sacred Places Sacred places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, Miegunyah Press at Melbourne University Press, 1999.

[9] The Memorial: A masterpiece of Aboriginal Art, exhibition catalogue, Musée Olympique Lausanne, 1999.

[10] Ace Bourke, 2008, op cit., p. 11.